8. Concurrency and Parallelism

8.1. Description

Effectively decomposing a problem so it can utilize multiple threads or multiple processes requires fully understanding a few concepts. One of which is the difference between concurrent and parallel processing. The two are not equivalent and thus erroneously choosing the wrong paradigm could cause degradation in performance. In the worst case scenario this may send developers down a rabbit hole while trying to find ways to optimize the code.

8.2. Definitions

A job is the work that needs to be done on the smallest and independent chuck of data. Meaning the processing of the data should not rely on any kind of previous processing in order for multiple jobs to run together. For example, it would not be wise to implement a Fibonacci sequence calculator since each “job” requires knowledge of all data points. Alternatively, if you need to multiply by a scalar each element in a sequence of numbers, then this can be performed in parallel or concurrently since “job” only requires a single data point. For this article you can think of a “job” as a thread or process running on the CPU.

A context switch is the phrase to describe the procedure in which the operating system changes which job’s instructions get executed on a CPU’s core - said in other words, a CPU’s context (i.e. the CPU registers) is switched from one job to the next. Deep in the hardware level, this is where the registers and caches on the CPU are saved into RAM and another job’s state is created or restored into the CPU’s registers and cache. After which, a job can start or safely resume instructions exactly where it left off previously. Hardware in conjunction with the operating system can make this very quick, but it is still a non-free consumption of time. The operating system will try to reduce context switches as reasonably possible while still providing a fair amount of execution time across all waiting jobs. Regardless of a concurrent or parallel paradigm, context switches happen every time a job starts and stops executing on the CPU.

Concurrent processing is when a computer can perform multiple actions seemingly at the same time. Single-core CPUs can only perform concurrent operations because they physically do not have the hardware to perform two actions simultaneously. The operating system will run a program’s instruction on the CPU for a particular chunk of time. The operating system will then halt the program either when the time slice expires or when the program freely signals to the operating system it does not need the CPU for a relatively long amount of time, like slow I/O requests or explicit “sleep” or “wait” instructions.

Parallel processing is when a computer can actually perform multiple actions simultaneously. Multi-core CPUs have the ability to run programs in parallel. In the early days of multi-core systems, a single process can only run on a single CPU at any given time. But as hardware and software progressed, matured, and became more efficient, it is now possible for processes to run multiple threads on multiple CPUs simultaneously.

A process is the realization of an executable file from the hard disk. Simplistically, the operating will copy the executable file into memory and start executing the bytes of the file on the processor. A thread can be modeled in a way very similar to a process (e.g. execute an instance of code) but is encapsulated within a process. Because all threads live within a single process, they all share the same allocated resources the operating system gave the process. That includes all allocated memory, file descriptors, signal handlers, etcetera. It is not terribly important if you’re not familiar with all of those terms, but just keep in mind a “resource” allocated to one process is technically shared with all threads in that process.

8.3. Visualization

To better visualize the difference between concurrency and parallelism, let us take the following scenario as an example.

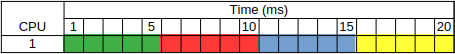

In this example there are four jobs: green, red, blue, and grey. Each job needs to perform some operation that will require 5 milliseconds of time on the CPU. The operating system could decide to execute the jobs linearly, as such:

The problem with this model is that three of the four jobs are starved CPU time. The grey job has to wait 15 milliseconds before it can even start. This problem is exaggerated even further when jobs run for much longer than a few milliseconds.

Scheduling algorithms in modern operating systems are smarter than this. The operating system will try to determine a fair and, close to optimal, way of giving each process some CPU time.

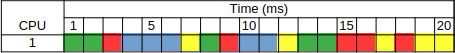

Assuming there is no overhead costs with context switching, let us pretend the operating system will give each job these time slices on the CPU:

- The green job runs for: 2ms, 1ms, then 2ms.

- The red job runs for: 1ms, 1ms, 2ms, then 1ms.

- The blue job runs for: 3ms, then 2ms.

- The grey job runs for: 1ms, 1ms, 1ms, then 2ms.

In a concurrent system the four jobs will be executed on the CPU as such:

As you would expect, the total time to execute all four jobs still takes 20 milliseconds. We did not get to complete all of the jobs any faster, but each job had the chance to start sooner at the expense of finishing a bit later. You might wonder why might any one want to ever use this scheme. For the decades when computers only had a single core CPU this is how all programs ran on the CPU. Think about it, a computer mouse needs a driver to interpret the signals from the mouse into real coordinates. Or a keyboard needs a driver to translate various signals from the many types of keyboards into character-codes. A monitor needs even more software to take the raw graphics and turn on the pretty little pixels inside a monitor. We cannot possibly expect a computer to do each of these operations in a contiguous manner. Each of these drivers need time on the CPU to reach the end goal of displaying a mouse roll over a link, or print characters in a word processor.

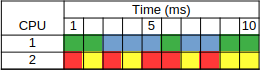

While a concurrent approach can only use a single core on a CPU a parallel approach will utilize multiple cores of the CPU. For simplicity, let’s say the operating system’s algorithm for choosing a CPU for a job is the “round robin” approach. Each new job that is created will use the next CPU in the sequence, then loop back when the number of CPUs has been exhausted. For our four job example, the green and blue jobs will run on CPU #1 and the r ed and grey jobs will run on CPU #2. Running the jobs might look like this:

In the parallelized case we cut the total time in half. All jobs will be complete within 10 milliseconds.

8.4. Application

All of this is to say developers should understand how processes and threads work for the language they are writing in so they can write code effectively. If a developer assumed their code is running in parallel but in fact was running concurrently they may spend a needless amount of time debugging a “code takes too long” problem. Conversely, if the developer assumed the code was running concurrently but in fact ran in parallel they may spend an equally needless amount of time debugging the elusive “race condition” that only sometimes appears.

8.4.1. Java (Threads are Parallel)

It is rather difficult to implement a truly concurrent processing in Java. For all intents and purposes, threads in Java run in parallel to one another. The Java virtual machine and the operating system will run a single process’ multiple threads on multiple cores.

8.4.2. Python (Threads are Concurrent, Processes are Parallel)

Python takes a different approach than most other languages, specifically the

CPython implementation whereby threads will run concurrently and processes will

run in parallel. In most other languages both processes and threads run in

parallel. Again, this is not the case for CPython. For historical reasons, the

memory model inside the CPython implementation had not been designed to handle

parallel processing safely and thus the Global Interpreter Lock (a.k.a. GIL) was

created. When a thread begins or resumes execution it locks the GIL which will

effectively prevent any other threads from running simultaneously even if the

hardware has multiple cores. To work around the GIL in a parallel manner, you

must run code within multiple processes. The Python multiprocessing module

makes this incredibly easy, but it does have draw backs that will be discussed

on separate pages.

This does not make Python threads unsuitable in all cases, I will discuss on a separate page where Python threads can be used efficiently.